maud's essays

Tribberly & Quonk

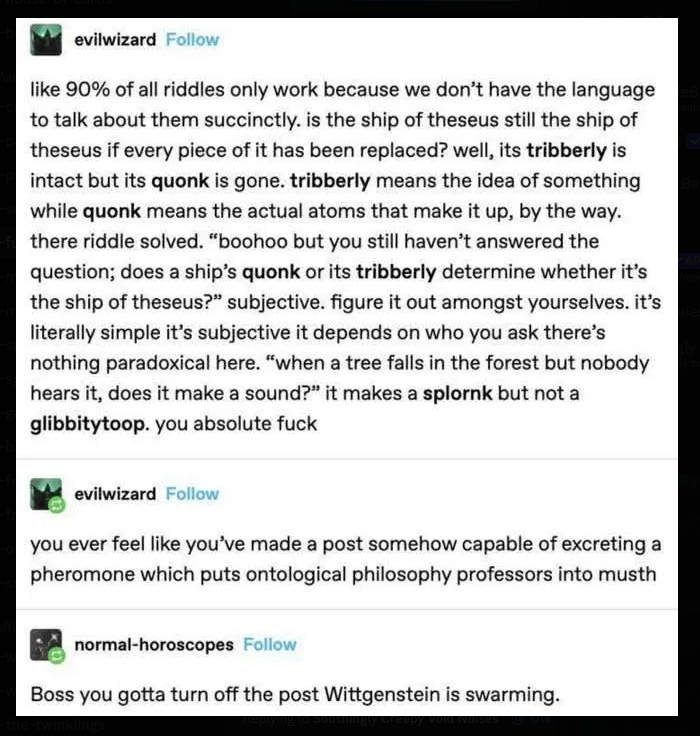

This meme is a humorous reflection on riddles, paradoxes, and philosophy. At the core of this meme there is truth. It's a riff on language. It's fun, it's cool, we're all happy. My first reaction to it though, was to attack. This reaction is not appropriate.

What's that, hey guys, it's me, I have a Philosophy degree. Four years of pondering issues of the day like zebra-painted-donkeys, 4D Space-time worms, and what it's like to be a bat. When all was said and done I submitted an 8,000 word dissertation on the concept of groups and left university feeling dejected with regards to pretty much everything that had happened. I don't feel like I understand philosophy, there’s too much of it. I don't feel like I truly understand anything.

One thing that’s changed since then, for whatever it’s worth, is that I feel less naive. And one thing I do understand is how to provide a serious analysis of the tribberly & quonk solution to the Ship of Theseus problem. In doing so I hope to show that we cannot question the meaning of life.

The Tribberly & Quonk solution to the Ship of Theseus problem

The post claims that we don't have the language to talk about the Ship of Theseus succinctly, and that the titular tribberly and quonk are necessary to fill in the gaps and explain whether Theseus’ ship is the same ship after having each and every part replaced over the course of time. The solution to the problem is said to be subjective, either of the two, or some combination thereof, depending on who you ask.

But do we lack succinct language for tribberly and quonk?

In the case of ‘quonk’ we do already refer to the boat’s parts, matter, or components, and the idea that parts of something could be interchanged is not mysterious, it is core to understanding the problem. The Ship of Theseus, in essence, is this question;

How can an object persist after having all of its parts (quonk) changed?

In the case of a ship perhaps we can easily admit to ourselves that the ship has not persisted, and sidestep the problem entirely. We tend not to care too much about exactly what ship any given ship is. For Theseus we can charitably grant that he and the people of Athens have attended to a continuously changing collection of planks, nails, rope, cloth, and tar (amongst other materials, I’ve never built a boat), and that they are allowed to call this the ship of Theseus. Everyone is happy, even if the ship has become a new ship before our eyes as it’s quonk is obliterated.

But what if some intrepid fellow, upon hearing that Theseus’ ship was made completely of replacement parts, tracked down every original plank, nail, length of rope, and tattered piece of cloth, and reassembled the ship. He then sails the ship into Athens and proclaims, “You have all lived a terrible terrible lie, for this is the true ship of Theseus, and that is nothing but a replica.” Once again, we might sidestep the problem by simply shrugging and commending said fellow on his accomplishment. Both ships may be called the ship of Theseus, nothing terrible would happen. Some people may disagree over which is the true ship, but neither ship is unworthy of reverence. Here, the exact relationship between an object and it’s parts is simply not important.

But what about people? Every single day your body replaces billions of cells. At some point, you will be composed of an entirely new set of cells. It feels much harder to say that you are not literally the same person as when you were a baby, and it feels far more important that we can point to how a person persists across time.

Arguably we might try to sidestep the problem as before. Frankly, it is correct to say that these questions are not really worth asking, and I will get onto that later. But, for now, let’s assume that this is, at the very least, a question worth asking; If quonk not an object make, if an object is something other than the parts which make it up, then what?

Could it be tribberly? The idea of an object? It feels very natural to say that Theseus has a strong idea of his ship and the parts which comprise it. Over time, after Theseus is long gone, enough people continuously apply the idea to the collection of parts as they change, and so the ship of Theseus is sustained. Someone who had been part of the crew for the ship’s entire existence would have no problem conceiving of how the ship had changed whilst remaining the same ship.

With people, though less clear, we can imagine the same principle applying. I cannot provide an exhaustive list, but roughly speaking people are amorphous bundles of memories, documents, body parts, and relationships. We persist as people, rather than creatures, in part due to the fact that we are recognised as such by others. We are born into this world with people having all sorts of ideas about us, and eventually we come to have many ideas about ourselves. We can point to things that exist and have happened, and know that they belong and have happened to the same individuals through time.

Nothing feels wrong here. We are humans and we classify things, sometimes imprecisely, and that process does not need to be precisely modelled. We can, as the meme suggests, figure it out amongst ourselves. If you present the Ship of Theseus problem to your loved ones they will more than likely say something similar.

Our understanding of objects and how they persist through change is tacitly understood, it is reflected in how we speak. Perhaps if you stare at a boat for long enough, and have a deep familiarity with timber, you could perceive the boat as merely a collection of parts, understand that no original piece remained, and thus come to some higher understanding about the true identity of Theseus' ship, but this is not how our brains evolved to work. It would be an unusual thing to do.

Arguably the best solution to the Ship of Theseus, and all it’s bastardly variants, would to be say, “That, nor anything like it, will never happen, and if it does it will be a helpless novelty. It is not necessary to reinvent our conception of something based on a hypothetical edge case, and so we should simply continue on as before.” But this is Philosophy and that cannot be allowed to happen.

Rationalism is one of the worst ideas anybody has ever had

Rational philosophy fails, mostly, to say anything useful about boats or people. Rational philosophy, or rationalism, stretches back to antiquity, and is the idea that reason is “the chief source and test of all knowledge”. Through thought alone we ought to be capable of making true statements about the universe and our state of existence. Statements that are either completely independent or only partially reliant on our experience of the external world. We can, for instance, know that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line without doing any measurements.

The most well-known of the rationalists, Monsieur René Descartes, provides the quintessential rationalist argument. He suggested that it would be perfectly possible for an evil demon to deceive you at every turn. To cause you to hallucinate with all of your senses to the extent that you would be unable to distinguish reality from a dream. You would never know that the demon were deceiving you, you would be living your life as you are now, and the true nature of your existence would be entirely withheld from you.

Under these circumstances, it turns out that it’s impossible to know practically anything at all. The external world cannot be trusted, even the contents of your own thoughts may have been corrupted, you may not be able to trust your memories or basic facts about existence. But, Descartes says, there is hope. The very fact that you are experiencing your own thoughts is definitive proof of the fact that something must exist to think them. Hence Descartes' most famous maxim;

“I think, therefore I am.”

Once we discard everything that we cannot be entirely certain of, this is what we are left with. The mere fact of our own existence. We can no longer trust the physical world, our loved ones may not truly be there, an evil demon has perched upon us. This is unacceptable, plainly we are capable of knowing far more than that, so what can we do?

Descartes, what with it being 1641 in Europe, argues that we have access to truths about the material world through God. A benevolent, powerful God would not permit a demon to deceive us so thoroughly, and through communing with God we are sure to have access to a whole host of tasty truths, real truths, about the world, our friends, the moon, and the sun. And, to be honest, all other things being equal, I don’t mind it. If there turns out to be a God, or Gods, or some eternal being that shapes our world, then that ought to be good fodder for founding a conception of truth and certainty.

As the history of western philosophy goes, however, the work of Descartes no doubt gave it a particular bend. Rational philosophy sought to cleave a neat separation between what is true and what is fallible, and to found this separation on a divine conception of truth. For Descartes the physical world, if you don’t accept the christian God, is fallible.

Rationalism effectively says; if you cannot provide some justification independent of your lived experience, derived from reason alone, then perhaps we ought to abandon your idea entirely because otherwise it will not be fertile ground for making true statements about the world.

It is the pathological reduction of all assertions, beliefs, and practices, into this notions of truth, falsehood, right and wrong that helplessly abstracts from how we actually conceive of objects, the world, and ourselves. In the real world, we deal in ambiguity and metaphor, relativistic ethics, perception, and emotion. Peoples and cultures emerge without absolute conceptions of truth and falsehood baked into their discourse, and they are sustained with justification that goes so far beyond solely what is immune from being debunked in the abstract. Religion, ritual, cultural and social norms, can all only be fully understood from the perspective of those who practice and experience them.

In this sense, rationalism tends toward prescription rather than description. Fundamentally, the project of rationalism was to determine what is true according to reason. According to rationalism, reason itself is a uniquely European and Christian virtue. Rationalism, and the nations which it guided, sought to correct people’s conception of the world and their place in it according to their doctrine. It is in this vein that rationalism was so sinister.

Rationalism is pervasive. It creates an immutable conception of what is correct in ethics, politics, religion, and culture. Placed in its historical context, the peak of rationalism as a dominant school of thought coincides with the height of “western enlightenment” during the 17th and 18th centuries. The rationalist conception of virtue, of what is right, correct, good, and true, provides the ideological basis for racial hierarchy, enslavement, repression and outright replacement of peoples deemed to live and exist in a way contradictory to reason.

It is this underlying ideology which guides who and what is considered heretical and savage, because ultimately the spread of enlightenment is right and the ends justify the means. Rationalism is a European invention, it is the instrument Europe used to justify it’s belief systems and structures of power. Because if your truth and falsehood, right and wrong, are immutable, and ordained from God, then they cannot be justly challenged.

Analytic philosophy is hostile and confusing, if you’re into that sort of thing

Whilst Rationalism has long shrivelled and died as a dominant school of thought, it lingers. Analytic philosophy, broadly speaking, is the contemporary philosophical zeitgeist. It emphasises clarity and analysis of language as a means of solving philosophical questions. To comprehensively answer a philosophical question you must agree on relevant definitions, unpack the question into constituent parts, and, whenever arguing any point, as far as is possible, ensure that your argument follows the structure of sound formal logic. It emerged in step with secularisation in opposition to rationalism as an ideology.

Whilst analytic philosophy is no doubt distinct, the rationalists established traditions that doubtless persist to this day. Analytic philosophy’s adherence to a binary conception of truth, and refusal to incorporate emotion or first-person experience as fundamental aspects of our existence, unquestionably trace their roots to rationalist schools of thought.

It turns out that amongst the neatest solutions for the ship of Theseus are the aforementioned 4D space-time worms. Objects are conceptualised as extending through 4D space, capable of gaining and losing physical parts whilst persisting through time. Whilst I like this idea, I don’t feel that I, and indeed most people, could be best described as space-time worms. When considering the identity of an object, it is seldom relevant to consider which of it’s parts were there when the object was first created. Ordinarily, people think about objects in terms of function and sentiment. Our conception of selfhood, for ourselves and others, is defined by us as many things, but seldom worms.

The vast majority of philosophy courses within universities are taught through the lens of analytic philosophy. Aside from being the dominant school of thought in academia it is, from a practical standpoint, the easiest to teach, debate, and comprehend. It is, however, cold. It will never provide the full picture that many people hope for from Philosophy. There is a helpless abstraction from what is actually experienced. How people truly interact with the world.

Analytic philosophy offers little clarity for ordinary and fundamental questions about our place in the universe and the nature of self, only endless questions, and consequently an adherence to it will leave you feeling as if those questions are valid but have no good answers.

Philosophy struggles to explain what things are

So then let’s go rouge. Tribberly and quonk. If we can just make up words that whenever we want to to fill in the gaps, why is philosophy still considered a serious discipline? How was it ever allowed to progress beyond slurred conversations over caskets of wine? Might it not all just be nonsense? Can we all just relax?

If you’d have waltzed up to René Descartes in 1641, after reading his silly book, and said, in French; “No René Descartes, you unforgivable goose, you’ve got it all wrong. There’s no evil demon, you’re just interrogating your bongle. Your bongle is all of the things we need to take for granted in order to make sense of the world. It includes the reliability of our sense-data, and the guarantee that other people are actually real. Whenever you interrogate your bongle, everything falls apart and you end up not being able to know anything, so you shouldn’t do that.” Straw-men notwithstanding, have you actually achieved anything here?

Other than time-travel, arguably not. For René, his conception of bongle is entirely wrapped up with his understanding of God. You and René both agree on the definition of bongle, but the concept has radically different meanings and implications for each of you.

Similarly, we might imagine that what an objects tribberly (the idea of an object, keep up) actually is could be understood as radically different by two people with differing perspectives. One society may determine object-hood as a result of a ship’s ownership, another may as a result of the ship’s design, but nevertheless these two tribberlies are united in that they are tribberlies. How can we hope for clarity in such circumstances? If a concept as basic as objects turn out to be so disgustingly relative, how can we determine the meaning of anything? Once again, perhaps we can figure it out amongst ourselves.

If you are existentially unwell, as I was at 18, the possibility that an evil demon could be deceiving you at every turn is deeply troubling, especially if you are unable to disprove the notion to yourself. If allowed to fester, this can severely damage your sense of reality. Indeed, a significant number of people believe, or are at least open to, the idea that we live in a simulation.

For stretches of time whilst at university I sincerely believed the world wasn't real and that I could prove it. I believed that we lacked certainty of anything beyond our own minds, including the minds of others. As such the external world had to be, in some way, comprised of our own minds, and so material things did not truly exist. Broadly speaking this was a poor interpretation of Subjective Idealism, a school of thought which is nevertheless enjoyable.

With a fuller understanding of what I had been exploring, if my attendance had been somewhere north of 30%, then I might have explored the problem of other minds in greater depth and come to a conclusion that I felt comfortable with. But I did not do that, and found myself neck deep in some dense wet mass of confusion, detached from the world and myself as a person within it. I worried intensely about tiny details, and tried to nourish myself to avoid pain, but none of it meant anything beyond what I decided, and I lacked the agency to decide much of anything. I felt I was playing along with a narrative that had been artificially crafted for me.

Radical scepticism of this kind, I think, is a position exclusively held by second-year philosophy students with the potential for undiagnosed complex post traumatic stress disorder. At it’s most extreme, according to a rather disparaging myth spread by his critics, Phyrro, a contemporary of Alexander the Great who maintained a principled indifference to the physical world, had to be constantly watched by his followers in order to prevent him from walking over cliff-tops.

Whilst radical scepticism has never been a strong tradition within western philosophy, scepticism of many flavours doubtless has. As we have seen, a rigorous analysis of a mundane concept like objects can leave you sceptical of the basic notion that anything or anyone is capable of persisting across time at all. This is no doubt healthy for the discipline of philosophy, but as an attitude for life it is somewhat unhelpful.

It is counter-intuitive for the vast-majority of people, even those with some background in philosophy, to atomise what is not typically atomised. Trying to isolate people, objects, their identity and existence, in the abstract, as parts or objects or animals or consciousnesses or what-have-you, will always be practically fruitless. Ultimately, tribberly and quonk represent yet another attempt to solve this unsolvable problem, to pin down what cannot be pinned down, and in doing so they abstract too far from lived experience.

When we stray so far from what things actually are, how things are experienced, how concepts are used in our language and minds, then we cannot ever hope to have a satisfactory understanding of them.

Wittgenstein, Wittgenstein, riding through the glen

Ludwig Wittgenstein in his posthumously published work Philosophical Investigations outlines his view of a language as being analogous to a series of games. More precisely, that speaking a language for the most part consists of various concrete activities and experiences.

He uses the example of two builders who use a basic language to co-ordinate their activity. The language consists entirely of words for block, pillar, slab, and beam. The first builder calls these words out, and the second builder brings the object that he has learned to associate with each object. Later, words for ‘this’ and ‘there’ are added to the language. The first builder now might communicate instructions in the form, “This block there”, accompanied with a gesture. Within this language, the meaning of each utterance is entirely bound within the activity of moving materials. Wittgenstein coins the term ‘language-games’, referring to the manner in which meaning within a language is determined by innumerable actions and activities. For Wittgenstein, languages that we encounter in the real world like English or German are loose collections of language-games.

We are capable of making statements with certainty about the world, “the sky is blue”, “that dog is red”, “Margaret Thatcher is dead”, but outside of their use in a particular context they do not say anything. The colour of the sky depends upon location and time of day. The dog being referred to may not literally be red, but auburn, or ginger, or a white dog under a red light. There may exist, somewhere, a woman called Margaret Thatcher who is not dead. The meaning of all these statements is dependent upon how the words are used in a given language, and ultimately the context in which they're uttered.

With regards to Theseus’ ship, the classification of objects is itself a language-game. The nature of objects, their supposed continuity through time, and the truthfulness of various statements about object-hood, are all determined by the usage of these concepts in our language. When we describe Theseus’ ship after it’s parts have all been replaced, there is a tacit understanding of the conditions that must be met for this ship in particular to be the ship of Theseus, and that is all that is required. We might imagine truth itself as being analogous to a game, one with a strict rule-set designed to ensure a mirroring between purported facts and reality. It is one that all languages participate in, it is fundamental to successfully navigating the world.

Within this framework, what can we say about the meaning of life? What about evil demons that deceive us at every turn? How can we objectively evaluate the truth of any statement if the means by which we express truth are dependent on something as flimsy as a game? Are we not still scrambling for some ultimate certainty, some objective truth that transcends our present feeble human understanding?

The hard limit that Wittgenstein proposes is that language is not some all-conquering force capable of unearthing hidden truths about our reality, but rather it is an inherently ambiguous and relativistic method of communicating sensible facts, concepts and ideas. As such, when we ask the question, “What is the meaning of life?”, we are not really peering behind the curtain at anything in particular. In essence, we are misusing language. The answer to this question must be experienced, it cannot be properly addressed in the abstract.

What is “What is the meaning of life?”?

The most common answer to the question is to say that life has no inherent meaning or purpose, and that you must create that purpose for yourself. But determining your own meaning for life is not something that can be done through clever manipulation of language, propositions, truth, and formal logic. It can only be properly done in the material world, with other people, through community and thoughtful action. In this sense, all of Western Philosophy ought to be seen as, in part, a complete abstraction from language’s intended purpose. Language, ultimately, evolved as a means of communicating facts about the external world. The meaning of life, should there be one, does not fall into this category. As Wittgenstein puts it in his work Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus;

“We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Of course there is then no question left, and just this is the answer. The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem. Is not this the reason why men to whom after long doubting the sense of life became clear, could not then say wherein this sense consisted? [...] There is indeed the inexpressible. This shows itself; it is the mystical.”

The principle issue with western Philosophy is that it will trick you into thinking the answer to philosophical problems must take the form of expressible language. This is the fundamental issue at play with the Ship of Theseus, it presupposes that there is a metaphysics, expressible through language, that can be exposed with rigorous interrogation. Analytic philosophy’s response to the question is, ultimately, a blind alley. All it can possibly hope to do is uncover the ambiguous nature of our language and experience. So too with the question of life’s meaning. The question presupposes that the answer to the question is expressible through language.

If your life is full of suffering, you are alone, and you are removed from meaningful activity and community, then no doubt the question becomes more relevant, and the want for an answer that presents itself neatly in the form of language is more palpable. The antidote is not to rip apart the foundations, and interrogate your own position in the world, but to seek out the things that make life feel as if it has meaning and purpose. That itself is the answer to the question. Wittgenstein concludes;

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”